Jess Anderson, DVM

When I was a kid, I don’t think I’d ever seen a bicycle helmet. There were no car seats for children. In the summer, it was pretty normal to see a pickup truck driving down the road with a group of kids sitting in the bed. Fortunately, things have changed. We are much more aware of the risk of traumatic injury and have better safety standards and practices in place.

The same is true of dogs. While you still see dogs riding in the beds of pickup trucks occasionally, it is much less common now than years ago. Leash laws mean fewer dogs roam the streets unattended. As a result, veterinarians see far fewer broken bones than in years past. It is inevitable however, that some dogs still escape the yard and get hit by a car, or jump out of their owners arms and just land wrong. Broken bones still occur.

Most of us have signed a friend’s cast or two when we were kids — someone who bounced off a trampoline and broke an arm, or twisted their leg wrong on a flight of stairs and broke an ankle. As a result of seeing casts so frequently used on humans with broken bones, most humans expect a cast will be used on their pet when they are diagnosed with a broken bone. While casts and splints are used in veterinary medicine to treat fractured bones, the majority of fractures seen in veterinary medicine are not amenable to healing with a cast; most require surgical stabilization for a good outcome.

Stabilizing a broken bone with a cast will generally result in a good outcome if the following conditions are met:

- The fractured bone ends have not moved much at all relative to one another — that is to say that the fracture is not displaced.

- The joint above and the joint below the fracture can be immobilized by the cast or splint.

- The activity level of the patient and the forces on the fractured bone can be minimized for a long enough period of time for the fracture to heal.

- The fracture is anticipated to heal fast enough to minimize complications from using the splint or cast.

Minimally Displaced Radial Fracture

While fractured bones in people, especially in children, frequently meet these criteria and are amenable to stabilization using a cast, the vast majority of fractures involving the limbs of animals do not meet these criteria, and require surgical stabilization. Most of the fractures we see in veterinary medicine are highly displaced, and it is impossible to line the bone ends and use a cast to keep them there.

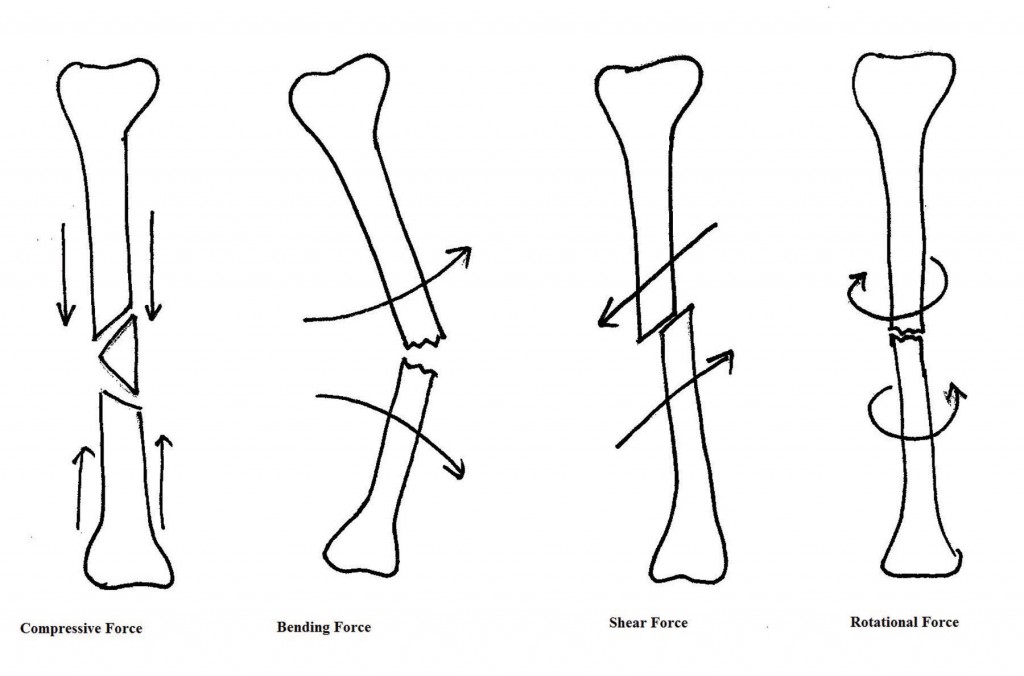

There are four types of force that are active on most fractures: bending, compression, rotation, and shear force (figure 1). A cast only offers moderate protection against bending forces, and no protection against other types of force. For a cast to be successful, the fracture must be resistant to the other forces by itself.

Figure 1 Forces on a fracture

Because surgical repair of fractures can be expensive, there is a temptation to push for trying to heal a fracture with a cast or splint when it is not a good candidate for this method of healing. When a fracture that should be repaired surgically is splinted or casted, the result is generally malunion — poor alignment of the fracture when it is healed that may significantly affect use of the limb, or non-union — the failure of the fracture ends to heal together at all. There may also be the temptation to “try” a splint or cast before surgery. The problem of delaying surgery when it is need is that the outcome is less likely to be satisfactory when surgery is significantly delayed. The fracture ends and the surrounding tissues begin to remodel quickly and are more difficult to realign when surgery is delayed.

Even in cases where a splint or a cast is an acceptable means of stabilization, the cost of splinting or casting is not insignificant as both generally require fairly frequent recheck exams and reapplication. Rub sores and other soft tissue injuries are also common sequelae to using cast and splints.

Fortunately, advances in techniques for fracture repair make successful outcomes possible for most pets with fractures, even those with very bad fractures. Hopefully your pet will never need to have a fracture repaired, but I hope this is useful information on why surgical methods of stabilization are so often required with fractures in dogs and cats.

Image 1 Minimally displaced fracture of the foreleg of a young dog. This fracture would heal well with a splint or cast.

Image 2 Complicated fracture of a large dog who was presumably hit by a car. This fracture required surgical stabilization using a plate.

Image 3 Fractures of both femurs of a kitten.

Both fractures required surgical stabilization using an external skeletal fixator.